Learning about the world’s toughest cancer.

Pancreatic cancer is a type of cancer that begins in the tissues of the pancreas—an organ located behind the stomach that helps with digestion and blood sugar regulation.

Table of Contents

About Pancreatic Cancer

What is the Pancreas?

Types of Pancreatic Cancer

Possible Risk Factors

Signs and Symptoms

Diagnosing Pancreatic Cancer

Treatment

Chemotherapy

Radiation Therapy

Other Treatments

Pancreatic Cancer Genetics

Genetic Testing

Clinical Trials

What is the Pancreas?

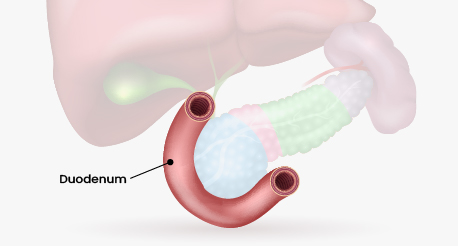

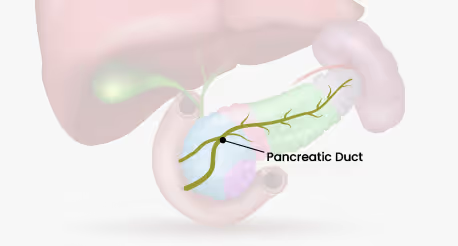

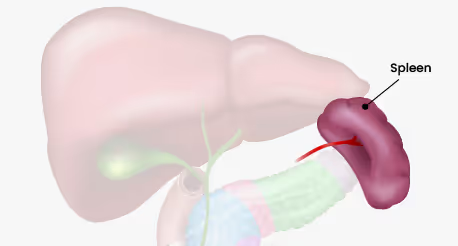

The pancreas is an important organ deep in the upper abdomen (belly), behind the stomach and in front of the spine. It is positioned among other organs like the liver, gallbladder, stomach, duodenum, and spleen. It is about six inches long and is divided into four main parts. Explore the pancreas below to learn about the different parts and their functions.

Understanding the Pancreas

Hover list to explore:

Pancreas

- The head is the widest part of the pancreas, on the right side of the belly, tucked in the curve of the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. The uncinate process is the part of the head that hooks towards the back of the belly around important blood vessels.

- The neck is the narrow part of the pancreas that connects the head to the body.

- The body is the middle part of the pancreas, between the neck and the tail. Important blood vessels run just behind this part of the pancreas.

- The tail is the narrow end of the pancreas on the left side of the belly, near the spleen.

Liver

The liver makes bile, a digestive fluid stored in the gallbladder that helps break down fats. It also processes nutrients from food and removes toxins from the blood.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder, a small sac beneath the liver, stores bile, a digestive fluid made by the liver, and releases it into the small intestine (duodenum) when fatty foods are eaten, helping the body break down fats and take in nutrients.

Stomach

The stomach stores food and churns it while mixing it with acid and enzymes to break it down. The partially digested food then moves into the small intestine (duodenum) for further breakdown and nutrient intake.

Duodenum

The duodenum, the first part of the small intestine, continues breaking down food from the stomach. It mixes the food with bile, a digestive fluid, and enzymes from the pancreas, allowing the body to take in nutrients.

Common Bile Duct

The bile duct is a tube that carries bile, a digestive fluid, to the small intestine (duodenum) to help digest fats.

Pancreatic Duct

The pancreatic duct is a tube inside the pancreas that carries enzymes to the small intestine (duodenum) to help digest food.

Spleen

The spleen fights infection, removes old or damaged red blood cells, and supports the immune system, helping the body fight bacteria and viruses and stay healthy.

The pancreas has two major roles: aiding digestion (exocrine function) and regulating hormones (endocrine function).

Digestion (Exocrine)

Most of the pancreas is made up of exocrine tissue which makes digestive enzymes. Enzymes help break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, allowing the body to absorb nutrients from food. The pancreas also releases a substance called bicarbonate, which neutralizes stomach acid so these enzymes can work properly in the digestive system.

Hormonal Function (Endocrine)

The pancreas also plays a key role in regulating blood sugar by producing two important hormones:

- Insulin: lowers blood sugar after eating.

- Glucagon: raises blood sugar between meals or during fasting.

These hormones work together to keep blood sugar balanced, which is essential for energy and overall health.

Pancreatic Cancer

When cells in the pancreas start to grow uncontrollably, they can form a lump called a tumour and may spread to other parts of the body.

Types of Pancreatic Cancer

Exocrine Cancers

These tumours develop from the exocrine cells that produce digestive enzymes. They make up about 95% of all pancreatic cancers and include several types:

Adenocarcinoma

Also called ductal carcinoma, adenocarcinoma is the most common type, representing over 90% of pancreatic cancers. It originates from the lining of the pancreatic ducts (small tubes that carry digestive enzymes to the intestine, where nutrients from food are absorbed).

Colloid Carcinoma

This is a rare subtype of adenocarcinoma that makes up one to three percent of exocrine pancreatic cancers. These tumours are surrounded by a jelly-like substance called mucin, making them less likely to spread and often easier to treat than other types.

Acinar Cell Carcinoma

This rare cancer develops from the enzyme-producing cells of the pancreas and accounts for one to two percent of exocrine tumours.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

This extremely rare form of pancreatic cancer arises in the pancreatic ducts and consists entirely of squamous cells, which are not normally found in the pancreas.

Adenosquamous Carcinoma

This is a rare tumour making up one to four percent of exocrine pancreatic cancers. These tumours show features of both ductal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. These have poorer outcomes than adenocarcinoma.

Neuroendocrine Pancreatic Tumours (PNETs)

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (PNETs) make up about five percent of pancreatic cancers. They develop in the hormone-producing cells of the pancreas called islet cells. Because they originate from different cells and behave differently than exocrine tumours, PNETs have distinct symptoms, progression, and treatment options.

PNETs can be either functional (producing hormones) or nonfunctional (not producing hormones). Most PNETs are nonfunctional. They are categorized by the hormone they produce, including:

- Gastrinoma (produces gastrin)

- Glucagonoma (produces glucagon)

- Insulinoma (produces insulin)

- Somatostatinoma (produces somatostatin)

- VIPoma (produces vasoactive intestinal peptide)

- Nonfunctional Islet Cell Tumour (does not produce hormones)

Possible Risk Factors

Risk factors are characteristics that increase the chance of developing a disease. Many factors can increase a person’s risk of developing pancreatic cancer, such as genetics (inherited traits), environmental exposures, lifestyle, and overall health. While some can be modified, like smoking or diet, others, such as age or genetics, cannot. It is important to note that having one or more risk factors does not mean a person will develop pancreatic cancer.

Tobacco Products

Smoking cigarettes is the strongest and most well-established risk factor. Smoking is a major preventable risk factor for pancreatic cancer, and quitting reduces this risk over time. Cigar smoking is also strongly linked to an increased risk but studies on pipe smoking and smokeless tobacco, such as chewing tobacco and snuff, have mixed results. Although vaping has fewer, harmful chemicals than traditional tobacco products, it still has nicotine and other potentially harmful substances that may increase the risk of pancreatic cancer. More research is needed to understand the link between vaping and pancreatic cancer.

Obesity

Obesity, especially belly fat, is a well-known risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Extra fat causes inflammation which can damage cells and lead to cancer. It also makes the body less sensitive to insulin, so the pancreas must make more, which can help cancer grow. Fat also changes hormones and can build up inside the pancreas, adding to the risk. Maintaining a healthy weight through diet and exercise is important to lower risk, especially since obesity is also linked to diabetes and chronic pancreatitis, both of which increase risk of this cancer.

Diabetes

Diabetes, particularly type 2, is associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer. This increased risk may be due to shared risk factors such as obesity, or because diabetes can sometimes be an early symptom of pancreatic cancer. While the association is well-documented, the exact relationship between diabetes and pancreatic cancer is not fully understood.

Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis is long-term inflammation that damages the pancreas, causing scarring and reducing function. This can increase the chance of abnormal changes and cancer. Repeated episodes of acute pancreatitis (sudden, severe inflammation) may also increase risk.

Heavy Alcohol Use

Drinking large amounts of alcohol regularly can damage the pancreas and cause ongoing inflammation (chronic pancreatitis). Limiting alcohol can help reduce inflammation and the associated cancer risk, making it an important lifestyle change.

Family History of Cancer

A family history of cancer, especially pancreatic or related types like breast, ovarian or colon cancer, can increase risk of developing the disease because of inherited genetic factors.

Other Risk Factors

More research is needed to understand the link between other risk factors, such as eating processed meats, occupational chemical exposures, bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), diet, gum disease (periodontitis), cystic fibrosis, physical activity, and blood type.

Signs and Symptoms

Pancreatic cancer usually does not cause symptoms in its early stages, making it difficult to detect. When symptoms do appear, they are often vague and can be mistaken for more common health issues.

Jaundice

Jaundice occurs when a tumour blocks the bile duct preventing bile, a fluid that helps digest fats, from reaching the small intestine. This causes bilirubin, a yellow substance found in bile, to build up in the blood. Signs of jaundice include yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes, itchiness (pruritus), dark urine and changes in stool. Stools may be pale or clay-coloured, greasy (steatorrhea) or oily, have a strong smell or float.

Pain in the Upper Abdomen or Back

This pain may feel like a dull ache or pressure in the upper belly, back or between the shoulder blades. It can happen because the tumour presses on nearby nerves or organs, such as the stomach, spine, or intestines. The pain may worsen after eating or when lying down.

Digestive Symptoms

The pancreas produces substances, called enzymes, which help break down fats, sugars, and proteins. If a tumour blocks these enzymes, food is not digested properly. This can cause bloating, gas, heartburn, or discomfort after eating, especially rich or fatty foods. Individuals may also have diarrhea or constipation. Other digestive symptoms include:

Loss of Appetite

You may lose your appetite or feel full quickly, even after eating a small amount of food. This can happen because the tumour slows or block parts of the digestive system, making it harder to digest food. This can cause nausea,bloating and vomiting, which can also lead to eating less.

Unintended Weight Loss

Losing weight without trying, even if your appetite seems normal, is common. When enzymes are not working properly, the body cannot absorb nutrients well, leading to malnutrition, and muscle and weight loss. Pancreatic cancer can also increase the body's energy demands, contributing to further weight loss.

Fatigue

Cancer-related fatigue is an overwhelming tiredness that does not improve with rest or sleep. This can result from the body using extra energy to fight cancer, poor digestion, weight loss, emotional stress or discomfort and pain that interferes with sleep. Cancer triggers the release of special substances, called inflammatory chemicals, which can also cause weakness and exhaustion.

New-Onset Diabetes

The pancreas makes insulin, a hormone that helps the body control blood sugar. A tumour can disrupt insulin production causing high blood sugar leading to diabetes. Symptoms include excessive thirst, frequent urination, blurred vision, fatigue, and weakness. Untreated diabetes can cause serious complications so it is important to manage it carefully.

Diagnosing Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic cancer is usually diagnosed using a variety of methods. The diagnostic process aims to confirm the presence of cancer, its location in the pancreas, tumour size and whether it has spread.

Medical History and Physical Examination

A medical professional will review symptoms, personal and family history of cancer, and risk factors. The physical exam may check for signs like jaundice, abdominal tenderness, or unexplained weight loss.

Blood Tests

Blood tests are important to assess overall health and look for signs that may suggest the presence of cancer. This can guide decisions about next steps.

Imaging Studies

There are various imaging tools to help diagnose pancreatic cancer. These include computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endoscopic ultrasounds (EUS).

Tissue Biopsy

A biopsy procedure is where a small sample of pancreas tissue is taken with a special needle. This sample is looked at under a microscope by doctors to see if there are any abnormal or cancer cells. The biopsy helps confirm whether the tumour is cancer or something else.

Pancreatic Cancer Staging

Following diagnosis, the cancer must be staged which helps doctors understand the characteristics of the pancreatic cancer, such as size and whether it has spread to nearby tissues or other parts of the body. This helps them choose the best treatment plan. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) uses the TNM system, which looks at three main areas:

T (Tumour): the size of the main tumour and whether it has spread beyond the pancreas

N (Nodes): whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes

M (Metastasis): whether the cancer has spread to distant organs

Doctors use these factors to assign an overall stage, from 0 to IV, which helps choose the best treatment approach.

Stage 0 (carcinoma in situ)

Abnormal cells are found but have not invaded deeper tissues.

Stage I

Cancer is only in the pancreas. Stage I is divided into the following stages based on the size of the tumour:

Stage IA: The tumour is two centimeters or smaller.

Stage IB: The tumour is larger than two centimeters.

Stage II

Cancer may have spread to nearby tissue, organs, or lymph nodes near the pancreas but not to distant organs. Stage II is divided into the following stages based on where the cancer has spread:

Stage IIA: The cancer is in the pancreas and has not spread to nearby tissue and organs or lymph nodes.

Stage IIB: The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes and may have also spread to nearby tissue and organs.

Stage III

Cancer has spread to major blood vessels near the pancreas and possibly nearby lymph nodes. It has not spread to distant organs.

Stage IV

Cancer has spread to distant organs, such as the liver, lungs, and abdomen, and may also involve lymph nodes or nearby tissue and organs.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the stage of disease, tumour location, overall health, and patient preferences. The goal is to cure the cancer by removing it completely. When a cure is not possible, treatment aims to control the cancer’s growth and improve quality of life.

Surgery

Surgery offers the best chance of cure but is only an option if the cancer is limited to the pancreas, with some exceptions, and has not spread. About twenty percent of patients are eligible for potentially curative surgery at the time of diagnosis.

Whipple Procedure (Pancreaticoduodenectomy)

This procedure is for tumours in the head of the pancreas. It involves removing the head of the pancreas, part of the small intestine (duodenum), bile duct, gallbladder, lymph nodes and occasionally part of the stomach. The remaining organs are reconnected to restore digestive tract function.

Distal Pancreatectomy

This procedure is for when the tumours is in the body and tail of the pancreas. The tail, parts of the body and spleen may be removed.

Total Pancreatectomy

This procedure removes the entire pancreas, spleen, gallbladder, bile duct, and parts of the small intestine and stomach. After surgery, patients require lifelong insulin and enzyme replacement.

Vascular Resections

In some cases, the tumour involves major blood vessels near the pancreas. This is a more complex operation requiring the removal and reconnection of blood vessels. Only select centers with specialized expertise perform these operations.

Palliative Surgery

When potentially curative surgery is not possible, surgery may be performed to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life. Palliative procedures can help manage things such as blocked bile ducts, which can cause jaundice, itching, nausea, and bowel problems.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses powerful drugs to kill the fast-growing cancer cells. Chemotherapy is a main treatment option and can be used at any stage of disease. Treatment is typically given in cycles with breaks to help the body recover. Chemotherapy can be given alone, or in combination with other treatments. The drugs can be administered intravenously (IV) or taken orally as pills.

Some chemotherapies commonly used include Gemcitabine, FOLFIRINOX (combination of four drugs: 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), Irinotecan, Oxaliplatin, Leucovorin), Abraxane, Capecitabine (Xeloda), Cisplatin and Paclitaxel.

While chemotherapy is an aggressive cancer-fighting strategy, it can also attack healthy cells which can lead to side effects. Depending on the type of chemotherapy drug and dosage, type of drug administration, and the individual’s general health, side effects will vary. Some side effects are mild and manageable, while others can lead to more serious problems. Common side effects include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, neuropathy (nerve damage often affecting the hands and feet), hair thinning or loss, changes in appetite, anemia, and changes in bowel habits.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy uses high energy rays or particles to targets and kill cancer cells. Modern techniques focus the radiation on the tumour to protect healthy tissue. In some cases, radiation is given with an oral chemotherapy to help it work more effectively. Radiation can also be used to help ease symptoms, such as pain. Radiation treatment can cause similar side effects to chemotherapy; however, because it focuses on one area of the body, additional side effects include skin irritation, abdominal discomfort, and bowel irritation.

Chemotherapy and radiation can be given at various stages in the cancer treatment:

Neoadjuvant treatment is given before surgery, typically to shrink tumours to make surgery more possible. Adjuvant treatment is given after surgery to destroy cancer cells that may be circulating in the body and reduce risk of the cancer coming back. Palliative treatment is used when surgery is not an option. The goal is to relieve symptoms and slow cancer growth.

Other Treatments

There are other innovative therapies including immunotherapy, which stimulates the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells, targeted therapies, which focuses on specific changes in the cancer cells and others that are currently being tested.

Pancreatic Cancer Genetics

Early detection of pancreatic cancer remains a significant challenge largely because there are no established screening guidelines for the general population. As a result, routine screening is not recommended for individuals at average risk. However, international guidelines recommend screening within research protocols for those at higher risk, such as individuals with a strong family history of cancer or certain genetic mutations (changes). These individuals may also benefit from genetic counseling to better understand their risk and guide medical decisions.

Sporadic Versus Hereditary Pancreatic Cancer

Most pancreatic cancers are sporadic, meaning they occur by chance without a known inherited cause. While all cancers involve genetic changes, not all are hereditary (passed down in families). About ten to twenty percent of pancreatic cancers result from inherited genetic factors. Identifying these hereditary cases is important because it can influence treatment options, help assess risk for family members and guide long-term surveillance strategies.

Certain clinical situations increase the likelihood that pancreatic cancer has a hereditary component. These include families with multiple members affected by pancreatic cancer, individuals diagnosed with pancreatic cancer along with another primary cancer, and those diagnosed at a younger age, typically before age 50. A personal or family history of cancers linked to hereditary syndromes, such as breast, ovarian, prostate, melanoma, or colorectal cancer, also suggests a possible inherited risk. People of certain ethnicities may have a higher prevalence of specific genetic mutations associated with pancreatic cancer.

Familial Pancreatic Cancer (FPC)

Familial Pancreatic Cancer refers to families where two or more biologically related individuals have been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, but no known hereditary cancer syndrome has been identified. FPC accounts for about ten percent of all new diagnoses of pancreatic cancer. Unlike some other hereditary cancers, there is no single gene identified as the clear cause of FPC.

Hereditary Cancer Syndromes Associated with Pancreatic Cancer

While no single gene mutation currently explains all hereditary pancreatic cancers, several well-known hereditary cancer syndromes increase the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. These syndromes involve specific genetic changes and often raise the risk of other cancers as well.

Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (HBOC) is commonly linked to breast, ovarian, prostate and pancreatic cancers.

Familial Atypical Multiple Mole Melanoma (FAMMM) increases the risk of both melanoma, a type of skin cancer, and pancreatic cancer.

Peutz–Jeghers Syndrome (PJS) is characterized by dark spots on the lips and digestive tract polyps, and increases the risk of several cancers including pancreatic, gastrointestinal, breast, and gynecologic cancers.

Lynch Syndrome (Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer, HNPCC) increases the risk of colon, endometrial, ovarian, stomach, and pancreatic cancers.

Hereditary Pancreatitis causes repeated inflammation of the pancreas, often beginning in childhood, and significantly raises the risk of developing pancreatic cancer over time due to chronic inflammation.

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) leads to numerous colon and rectal polyps and carries a slightly increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN1) increases the risk of tumours in hormone-producing glands, including pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours.

Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) Syndrome is linked to a higher risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours, as well as tumours in the kidneys, brain, spine, and adrenal glands.

Genetic Counselling and Testing

Individuals with pancreatic cancer or a personal or family history suggestive of hereditary pancreatic cancer should be referred to a genetics clinic or genetic counselor. Genetic counsellors are healthcare professionals with advanced training in medical genetics and counselling, which enables them to assess risk, order genetic testing and interpret results. Genetic testing can help determine if you carry genetic changes, which could increase your risk. The decision to have genetic testing is a personal one and it is important to make an informed choice. It is always a good idea to keep your doctor informed about your family history of cancer. A doctor can provide a referral to a genetics clinic or counsellor.

Risk Assessment

The genetic counsellor will review your personal and family history of cancer and any other relevant medical information. If previous genetic testing has been performed in the family, sharing those results can be helpful.

Education and Informed Decision-Making

There will be a discussion of hereditary cancer risk, inheritance patterns, available genetic tests, and how outcomes may impact you and/or your family. There may be information about screening for other cancers and prevention options. There will be an opportunity to ask questions and receive support to make an informed choice about testing.

Note: Genetic testing is voluntary. Genetic counselling is designed to provide information to support informed decision-making.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing involves providing a blood or saliva sample. The specific genetic tests will depend on personal and family history and the clinical situation.

Genetic Test Results

Test results can guide cancer risk management and treatment decisions, including eligibility for targeted therapies or clinical trials. If a mutation is found, family members may be offered testing. The genetic counsellor can then recommend appropriate screening, prevention strategies, or enrollment in research studies and high-risk surveillance programs. Ongoing health monitoring is essential, and any new or unusual symptoms should be evaluated by a healthcare professional.

Cost and Access Considerations

Genetic testing may be covered by health insurance, particularly when ordered for individuals who meet clinical eligibility testing criteria. Out-of-pocket costs vary by country, insurance plans, and laboratories. Turnaround time for results also varies by testing facility and type of analysis.

Finding Genetic Counsellors

Canada: Canadian Association of Genetic Counsellors (CAGC) ⯈

United States: National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) ⯈

Other Countries: Ask your healthcare provider or local cancer center about available options.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are research studies that evaluate new treatments, either alone or in combination with current standard treatments, to see if they are safe and effective. They are important for discovering new potential treatments for pancreatic cancer.

Clinical trials are available for various stages of pancreatic cancer and may be considered at the time of diagnosis or during treatment. Each trial has specific eligibility criteria that must be reviewed by the treating physician. It is important to determine whether the experimental treatment will be a better option than the standard treatment, while considering potential risk factors and side effects. Participation is voluntary and typically involves a screening process, treatment phase, ongoing monitoring, and follow-up care